Blog

“A hated, illegal and amoral affair”: the double life of a Buda physician in the 1880s

This post by Sándor Nagy leads us through an extraordinary story which demonstrates that the everyday family life of middle class people was very far from the ideal of the sentimental nuclear family of thew 19th century.

There are a number of stereotypes and myths about nineteenth-century families and family life that survive until today. There is a certain nostalgia when thinking of the multi-generational, multi-child “Victorian”-era bourgeois families that radiated strength, respect, and stability, and which were held together by the protective, wage-earning husband and the caring wife—who, as they grew gray, became respected old men and matrons. The wrecking of marriages, adultery, separation, and concubinage are incompatible with this image: “deviant” forms of married life tend to be associated with working-class couples of the period, even by historians.

However, the case of Richárd Vörös MD, a physician who lived in a “traditional” but economically booming part of Budapest—the neighborhood known as Viziváros—points to the fact that concubinage was not a “privilege” of those social classes thought to be morally inferior. A physician at the Saint John’s Hospital in the 1880s, Vörös played the role of the perfect husband at home in Viziváros. However, in the Pest side he built another, happier life in secret, in which he not only was a loving partner but at the same time a caring father. He was only uncovered years later, when a short letter which accidentally got into the hands of his wife left him no room to live a double life anymore. His lawful wife confronted him with a tipping point: it was either her or the “other” family. Vörös’s decision must have been hard: the conflict led to him leaving his wife, to a desperate lawsuit, and finally to the breakup of his marriage.

Vörös’s workplace, St. John’s Hospital stood at the Széna Square until the end of the 19th century. Source: Egykor.hu

Vörös’s workplace, St. John’s Hospital stood at the Széna Square until the end of the 19th century. Source: Egykor.hu

Richárd Vörös and Mária Popovics

The marriage that Richárd Vörös contracted with Mária Popovics in 1874 was one of many similar marriages of the period, which was not based on mutual affection but held promises to both parties. This was already the groom’s second wedding, as he was introduced in the Lutheran church register as “widower.” Aged only twenty-nine, he of course counted as young; furthermore, both his noble origin and family background—he was born into a rich merchant family from the prosperous Győr, a town close to Vienna—and his degree in medicine made him an attractive partner.

His fiancée Mária Popovics, despite being listed in the register as a maiden, was Vörös’ senior, as she was over thirty: she likely felt embarrassed by this, which is why she declared herself to be twenty-five. Yet Maria, who was born from the marriage of the Roman Catholic Katalin Lastschok and György Popovics—a “small merchant” and member of the important Eastern Orthodox Serbian community in the Buda part of the capital, on the right bank of the Danube—and owned one-third of the house at 14 Fő Street in the Viziváros, was an appropriate choice for a young physician who was about to settle in Buda.

Although the union did not produce a child for some years, the marriage seemed to function. At the very least, the German last will and testament that was registered in front of the public notary, Zsigmond Rupp, at the end of 1878 signifies harmony:

we undersigned spouses, Richard Vörös MD and Mária, born Popovics—in certification of our mutual, unconditional trust and devotion and led at the same time by our intention to express our communion in our wealth even after death—leave, after conscious consideration and in free will, the testimony in the case of our death as follows:

The content of the testament leaves no doubt about their mutual trust: they both named their spouse as inheritor of all existing acquired and inherited wealth they had.

Wedding photo from the end of the 19th century. Source: Fortepan

The last will and testament was valid for almost a decade, until Mária Popovics, attending the office of the Viziváros public notary on January 17, 1888, stated that:

the reasons that led me to name . . . my husband, Mr. Richard Vörös MD as my general inheritor do not stand anymore, and my will from that time does not fulfill my intentions anymore, therefore, I, the undersigned Mária Vörös, born Popovics, after conscious consideration withdraw the last will and testament in question in its entirety with the effect as if that last will and testament never came into being. In case of my death, based on that last will and testament my aforementioned husband cannot lay any claim to my inheritance.

What could have happened that led the wife to this drastic step?

Place of the Vörös doctor and the baptism of his children: the old Lutheran church in Buda on Dísz square

The story of Emma Breitzner

Around 1880 Richárd Vörös met Emma Breitzner, the wife of an Austrian military officer in the joint army of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, Ritter Wilhelm Lendl von Murgthal, a captain of the imperial-royal military engineers who was stationed in Budapest. Soon afterwards, she became the physician’s lover. There is no detailed information on the beginning of their love story: the only certainty is that when the woman, who by then was separated from her husband and lived with her two children, sued for divorce against Captain Lendl at the beginning of 1881, the affair was already in full swing.

Who was this woman and what brought her to the Hungarian capital? Emma Breitzner was born in 1855 in the capital of the Habsburg Empire, Vienna. She was not even six months old when she lost her father. Her marriage to Lieutenant-Auditor Rudolf Redl at the age of seventeen was probably due in no small part to her family’s precarious financial situation, but she was unlucky as two years later he died of heart problems aged just thirty-five. This marriage left no financial inheritance: only a common child, Rudolf, born in November 1872. After a grief year, the twenty-one-year-old widow married Lieutenant Wilhelm Lendl, from whom she had a daughter, Emma, born in March 1877. After that, she moved to her husband’s station in Hungary.

Initially, her husband rapidly ascended through the military ranks, but some years later his career ended badly. The issue of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy’s joint army and Hungarian national independence aspirations were constant sources of tension, and among officers with different origins and political opinions, these tensions could manifest in everyday life. The Austrian captain Lendl caused a sensation when, in the summer of 1881 during an argument at a restaurant, he provoked his Hungarian associate officer Lieutenant István Göczel to express patriotic thoughts, which were incompatible with the espirit de coprs of the joint army. Consequently, the court of honor deprived the lieutenant of his rank. The next round of the recurrent, sport-like Austrian-Hungarian quarrels of the Dualism was picked up by the press both in Hungary and Austria, which also led to the end of Wilhelm Lendl’s military career. Due to the politically delicate nature of the issue, he had to resign from his rank as an officer in October.

Uniforms of the technical units of the imperial and royal army. Captain Lendl could wear a uniform like left from the 3rd soldier

The well-known affair in the contemporary press correlated with the divorce petition initiated by his wife at the Royal Court of Law of Budapest. At the beginning of October, the newspaper Fővárosi Lapok (Metropolitan Papers) reported the following:

The ex-captain not only had a problem with István Göczel, but also had and has with his own wife. They have been separated for years, and now Mrs. Lendl, his wife, does not want to carry this mired name anymore and has petitioned for divorce.

However, it was not the scandal that aggravated the marital conflict, as the divorce suit commenced earlier, at the beginning of the year. In the breakdown of the relationship the husband’s debts may have played a more important role than his carelessness. At the beginning of 1880, for instance, a debtor called Mór Auspitz laid a claim for a debt of 2,300 florins against him: this single debt was more than double the captain’s yearly income.

After the deposition of Ritter Wilhelm Lendl von Murgthal, he left Hungary and was hired as a railway officer, living in Teplitz (Teplice), Silesia, until his death in 1912. In the ongoing divorce suit which his wife renewed at the beginning of 1883, he cooperated in dissolving the marriage.

Divorce was a complicated thing in the Monarchy at the time; it depended on whether the person was of Austrian or Hungarian nationality, the residence of the two parties, as well as their religious confession. Fortunately for the Austrian couple, they could conduct the divorce suit in Hungary as the officers of the joint army had dual citizenship: they also counted as Hungarian citizens. Moreover, unlike in Austria, in Hungary they could break the marriage up despite their Catholic faith, although they first had to convert to a confession which permitted divorce. The fact that both Emma Breitzner and Wilhelm Lendl did this (they both converted from Roman Catholicism to Lutheranism) suggests that the respondent did not want to discourage the divorce. As such, the Royal Court of Law of Budapest approved the divorce suit, referring to an “inveterate hatred,” at the end of 1883, and the Curia, the Hungarian supreme court of third instance, put it into legal force at the beginning of 1884.

Divorce trial in Victorian England.

Divorce trial in Victorian England.

The “concubinage” of Richárd Vörös and Emma Breitzner

From the divorce papers, only those decisions which provide little substantive information survive: as such, we do not know what exactly the two parties’ grievances were. The discontinuation of the lawsuit in 1881 and its renewal in 1883 indicates that cooperation between the couple was not smooth at the beginning. This assumption is strengthened by the second instance verdict:

The “inveterate hatred” can be well argued by the repeated mutual accusations of the parties involved, the already-initiated lawsuit, as well as the years of separation

We know from other sources that Wilhelm Lendl accused his wife of adultery, and it was probably the “fruit” of this liaison that caused the interruption of the first lawsuit. In the early spring of 1882, Emma Breitzner gave birth to an illegitimate boy named Elemér. It may have been her pregnancy that made her halt the divorce suit, which she continued only in January 1883. The baptism was held in total secret at the Lutheran Church of the Castle Hill. Apart from the pastor, only two people were present: the mother, and to officially replace the godparents, who lived in Lower Austria, one “MD Veöreös practicing physician.” The single mother remained silent about her marital status: she was entered into the church register as a widow. The secrecy is understandable, as if the truth was revealed, not only would the divorce suit have been endangered, but also the marriage of the blood father, Richárd Vörös.

Wilhelm Lendl’s move abroad, alongside the subsequent granting of the divorce, averted the danger of unveiling, and Vörös could continue his affair with Emma more calmly in the Pest side of the Hungarian capital, on the left bank of the Danube. Of course, they did not publicize their relationship, but after a while—as Mária Popovics later complained—rumors started to spread in the city. There are traces of their relationship in the church register of the Lutheran church of the Buda Castle. The aforementioned Elemér was followed by Tibor, and at least three further illegitimate children: Elemér, born in the year of the divorce (their first child bearing the same name had died by then), Gabriella, at the beginning of 1888, and finally Edit, in the spring of 1892. It is interesting that the nuclear family of Richárd Vörös learned about the relationship relatively early, as the second Elemér in November 1884 was held under the baptismal water by the grandparents, “Márton Veöreös, landowner” and Zsuzsanna Tüske.

We have only a fragmented image of Richárd Vörös’ everyday life, based on the papers of the divorce suit held at Kolozsvár (today Cluj-Napoca). Mária Popovics later declared that while his husband handled her with care and affection, at the same time

my husband played the constant and full role of the father of a family in the apartment of his lover. He visited her and their children every day, he supplied their kitchen with everything and made acquisitions for that [woman] for years.

In order to prove this, the wife asked Ferenc Lettner, the housekeeper of the couple’s common Pest flat at 15 Vas Street in Józsefváros, to bear witness. By the time of the divorce suit, Emma—probably because she was less notable there—lived in the noisiest part of the capital, Erzsébetváros, on the first floor of 74 Dohány Street.

The secret family life of Vörös doctor was on the Pest side:

intersection of Dohány Street and Erzsébet Boulevard around 1890.

Source: Fortepan/Budapest Főváros Levéltára

This, and other details emerged of course only after the affair was revealed and Mária Popovics started to investigate the unknown woman. It all began with a tragic family affair. At the end of 1887, Vörös’ mother Zsuzsanna Tüske (Dorn) died in Gergelyi, a village near to Győr, and the physician traveled home for the funeral. He had already arrived back in Buda, when on January 16, 1888, a letter—addressed to Vörös and forwarded to his address in Buda from Gergelyi, where it had originally been sent—arrived with the mail. As the physician was at work, it was handed over to the unsuspecting wife, who opened it. The following, German-language condolence letter revealed itself to the wife:

My beloved Richárd! I was grieved to read your lines in which you informed me of the death of your mother. Even if I was prepared for the news, it still deeply shook me. I would have loved to stand by you in this difficult moment of life to join my sorrow and tears with yours but unfortunately I had to be away from you. Take care of yourself dear Richárd, please do not indulge in pain, think of me and your children. As much as I feel sorry for your father, and he probably will have a hard time letting you go, I most sincerely wish and hope to see you soon in our circle. The children already keep asking where you are. Please convey my heartfelt hand kiss and all best wishes to your father, and I myself also deeply and sincerely share your pain for losing your beloved mother, as your mother was the grandmother of her and my children. And now, my beloved, dear Richárd, live happily, and I kiss you until seeing you again and accept my innumerable greetings. Your ever-loving Emma.

Naturally, Mária Popovics immediately started to ask who authored the letter; who would use such a confident tone with her husband. Through her friends, she made it to the couple’s apartment. The wife recalled the story of the odd winter evening in her divorce petition as follows:

After receiving the letter, many times my husband, coming home at around 10 complained how much he is being harassed by his patients and that he has no escape, while I saw with my own eyes through the window, that two hours before coming home, he was having his dinner in a good appetite at the Dohány Street flat of Emma Braitzner [sic] just like some sort of a head of household, as a husband with his wife usually does. And while sitting giggling, in joy, surrounded by his concubine and his illegitimate offspring, he did not know that his wife witnessed the whole scene.

The scene of the “official” family life of theVörös doctor: the view of the Water Town from the Castle around 1890.

Source: Fortepan/Budapest Főváros Levéltára

The Devil should take you!

This is how Richárd Vörös allegedly reacted when his wife challenged him, and after denying it, he was cornered. After that the physician left the house in Viziváros, owned by his wife, and never returned. The next day, the first thing his wife did was withdraw her last will and testament, favoring her husband, at a public notarynamed Zsigmond Rupp. She later brought a lawsuit for alimony at the district court of Buda.

The comfortable double life of Richárd Vörös was suddenly over, and the man faced a crossroads.

His wife would have taken him back if he “mended”: that is, he discarded his lover and “family.” Later at the court during her petition for divorce, Mária Popovics emphasized that her placability was not merely tactical. The physician could have decided to continue his life with Emma, but it seems that this solution under the new circumstances would not have satisfied the couple. The fact that Vörös finally chose the more difficult and costly legal solution allows the assumption that maintaining the illegitimate situation was tenable for Vörös only as long as the façade of his legal marriage helped to secure his social prestige, which was no longer the case. . Emma Breitzner’s wishes may also have influenced his choice, but the fact that the man did nothing to legitimize the relationship for eight years shows that the woman’s interest in this case was secondary. However, the legitimacy of his children may have been an important aspect, which was given even more weight by the birth of the physician’s daughter, Gabriella, only a week after the scandal broke.

The only way to legitimize the relationship and to settle the children’s legal status was by divorcing and remarrying.

Divorce became increasingly common in Budapest in the second half of the nineteenth century, primarily amongst middle-class couples. Indeed, Richárd Vörös may have seen a number of divorces in his own closer and broader circle. Indeed, Richárd Vörös may have seen a number of divorces in his own closer and broader circle, one example being his “first hand” experience concerning the twists and turns of his own lover’s divorce suit in the beginning of the 1880s.

This may be because divorce became significantly easier in Hungary from the 1870s: however, if spouses could not come to an agreement and went to court, it could become quite difficult. Of course, the last thing Mária Popovics wanted was to make things easier for her husband; as such, one could anticipate an unrelenting and bitter divorce suit potentially lasting years. Moreover, even the outcome of the procedure was questionable as the wife, unlike the adulterer husband, respected the contemporary marital norms.

The divorces ended up in the Supreme Court until the 1890s: the royal mansion is on Ferenciek Square.

The divorces ended up in the Supreme Court until the 1890s: the royal mansion is on Ferenciek Square.

The difficulties were enhanced by the mixed confession marriage, more specifically the Catholic faith of Mária Popovics. Richárd Vörös was Lutheran, and while Protestants, according to the 1783 marriage chart of the enlightened ruler Joseph II, were allowed to divorce, Catholics were not. These bonds were long considered just as indissoluble as Catholic marriages, but an act issued two decades earlier (Act XLVIII in 1868) allowed Protestants to divorce unilaterally. This, along with the liberal regulation of conversion, granted divorce not only to Protestant husbands and wives, but also to every wedded Catholic who was about to leave his or her spouse (which was how Emma Breitzner could get rid of Captain Wilhelm Lendl). However, if the respondent did not convert, the divorce suit had to be initiated at the responsible ecclesiastic court—the Holy See—and it was only after its legally binding judgment that the case could be transferred to the court of the claimant, which in the case of the Hungarian Protestants was the territorial state venue, the Royal Court of Law.

After considering all these difficulties, Richárd Vörös and his legal advisors opted for a special solution that contemporaries referred to as “Transylvanian marriage.” In the easternmost area of Hungary, the region over the Király-hágó (Pasul Craiului; this symbolic geographical spot was used to delineate the two areas), the territory of the former Grand Principality of Transylvania, divorce proceedings were not heard at the Royal Courts of Law, but instead at the centuries-old Protestant ecclesiastic courts. Compared to the areas west of the Király-hágó, divorce in this region was a much easier, faster process. Accordingly, from the 1870s onwards, married Austrians and Hungarians from across the Monarchy arrived in Transylvania, hoping to be freed so that they could remarry.

Among the Protestant courts, the Unitarian Kolozs-Doboka Subdeaconal Court of Law stood out for its “liberalism”; furthermore, its territorial jurisdiction oddly also included areas west of the Királyhágó. The physician therefore did not have to do anything else than to convert to Unitarianism—which he did at the end of January—and wait until he received the customary dismissal by the Catholic ecclesial court of his case, in which he petitioned to break up his marriage. His divorce suit was already at Kolozsvár in the spring of 1888.

Mária Popovics, as would be expected, withstood to the very end, as evinced by her counter-petition:

I testify that for the sake of the claimant, I did not reject my confession, so that he, the claimant, could better get along. I admit that I did not turn into a false Unitarian, as Richárd Vörös MD did, so that he could tear up the bond sanctified between the Lord and the world as fast as possible in order to sanctify another hated, illegal, and amoral relationship.

– in her counter-petition she demanded the dismissal of the divorce petition, or failing this, the “denial of bonding” (in Hungarian, “ligába vetés”; the prohibition of marriage with his “associate in crime”).

The Unitarians built a church in Budapest in Nagy Ignác Street between 1888 and 1890, at the same time when it was Vörös’s divorce.

Source: Fortepan/Budapest Főváros Levéltára

At the Unitarian court these arguments were usually ineffective, as the claimant only had to prove the decomposition of the marriage, which Richárd Vörös could undoubtedly do. However, in controversial cases—owing to the fact that in mid-1880s Hungary and Austria there were numerous attacks and critics against the overtly liberal procedure of the church forum—the court of second instance, the Decanal Court, was more cautious. Accordingly, at the end of 1888 the court, referring to procedural infringement, did not approve the subdeaconal court’s decision to break up the marriage. The physician had to restart the procedure at the Holy See.

Richárd Vörös found himself in a tight situation, as at the Holy See, Mária Popovics got the opportunity to prove adultery according to the rules of the court, which could have led to the failure of the new marriage and even to prosecution. Finally, after a year of wrangling, during the spring of 1889 both parties admitted that the escalation of the legal dispute could not lead anywhere, and so they came to an agreement on the coming steps. In a contract concluded in front of the public notary, Alajos Zimány, the husband obligated himself to comply with Mária Popovics’ financial claim of 2000 florins, as well as to pay a further 200 florins for her legal expenses. This was a huge sum; at that time, the physician’s annual salary only amounted to 1500 florins. However, in return the wife promised not to further impede the divorce: she would not call witnesses to the Holy See, she would not refer to adultery, and she would not request legal remedy.

The suit at the Holy See still lasted for more than a year, and it was only in the spring of 1890 that the case was again brought to the Unitarian court after the judicial separation of the wife. This time the Decanal Court did not set any further bar to the divorce and broke up the marriage of Richárd Vörös and Mária Popovics. (According to a Hungarian particularity, in the case of mixed petitions for divorce, separation was granted only to the Protestant party: the Catholic party remained legally married to the end of their life, or that of their former spouse.)

With that, all barriers to legalizing the “concubinage” and the children born from the relationship were eliminated. For unknown reasons, it still took more than a year and a half for the couple to get married. It is certain that Richárd Vörös returned to his Lutheran faith, and in the autumn he made an application to adopt his blood children Elemér, Tibor, and Gabriella Breitzner. In the meantime, a date had been set for the wedding in the Hungarian Lutheran church of Deák Square as the mayor’s office of the capital had already granted an excuse to promulgate the marriage, alluding to the fact that “the named persons are bound to an inconspicuous wedding.” However, the wedding was then cancelled.

The relationship of Richárd Vörös and Emma Breitzner may have been dogged by the years of insecurity and the financial losses of the divorce suit. If so, then by the summer of 1891 at the latest, they had reconciled, as in the spring of the following year their second daughter Edit was born. In the beginning of 1892 the adoption of the child was again on the table. By that time, however, there were other considerations behind the marriage plans: the pregnant Emma was suffering from terminal cancer. The marriage therefore did not carry the promise of a new happy married life, but could only offer the comfort that she would exit the world as a legal wife, not as a concubine. The ceremony was held only a week after Edit was born, on March 19: by April 1, the woman was dead, bringing an end to Richárd Vörös and Emma Breitzner’s twelve-year relationship.

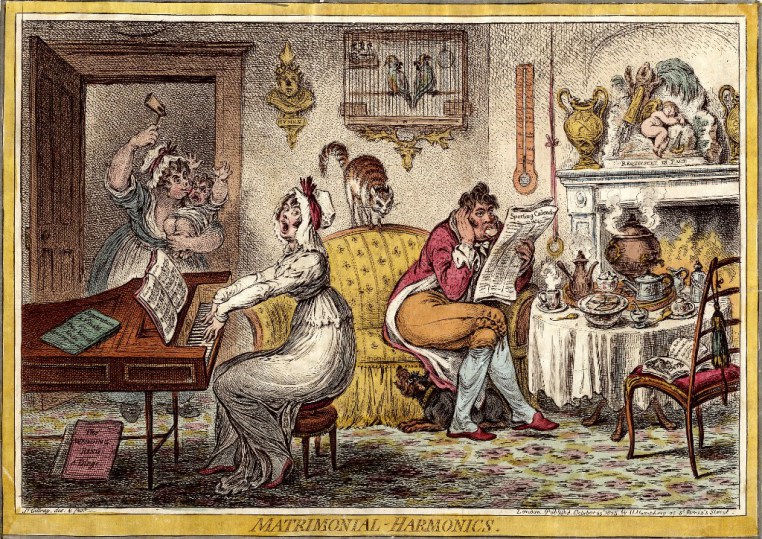

James Gillray made his cartoon series in 1805

about the “harmony” of the middle-aged couples in the city

The stepfamily

What could the lesson be? The spread of “concubinages” in the period may not reflect a crisis in the institution of marriage. Legal and social factors such as the indissolubility of existing marriage bonds, the regulations and costs associated with marriage and divorce, the social inequality between the parties, the disadvantaged situation of women, and the difficulties in settling the legal status of children all contributed to the changes in relationships. Growing secularization was another factor, incorporating both the weakening of religiosity and, conversely, the distrust and repulsion against the civic marriage introduced at the end of the nineteenth century. This is why the phenomenon may also have appeared amongst members of the middle class, who did not otherwise seem to prefer extramarital cohabitation.

Of course, it is difficult to tell to what extent middle-class men and women engaged in either brief or prolonged extramarital love affairs. It is likely that lasting “concubinages” similar to that of Richárd Vörös were rare, and became even rarer after the turn of the century; conversely, taking a lover or engaging in other forms of sexual relationship was more common. The decreasing importance of the barriers set by marriage may have played an important role in this, alongside the fact that the dissolution of marriage ties became legally possible and increasingly socially accepted. However, complications around the transmission of wealth remained an important retaining factor.

The case of Richárd Vörös and Emma Breitzner’s children illustrates that not even a loving and caring father could permanently hold together his “multicolored” family.

Not long after the death of his long-time partner and wife of two weeks, the physician met Erzsébet Mezey—the daughter of János Mezey, a notary from the countryside—whom he married at the end of the year. The spouseless man obviously needed a woman who could run the household and raise the six orphans of Emma Breitzner. While waiting for the wedding, the young bride indeed prepared for this role. In the letters written to Vörös, the topic of the children arose a number of times.

When the physician had two children from his marriage with Erzsébet (a son, Andor, in the autumn of 1893, and a daughter, Ilona, at the end of the following year), the couple had altogether eight children from four different relationships to take care of. By 1895, the eldest, Rudolf, was already twenty-three, while Ilona, the youngest, had only just turned one year old.

After Emma Breitzner’s death, the children from her first two marriages received their (motherly) inheritance and became independent within a few years. Rudolf Redl soon fell out with his father and left the family circle. In 1897, Emma Lendl became the wife of a northeastern-Hungarian Calvinist pastor, János Pap. The rest of the children, Tibor, Elemér, Gabriella, and Edit, could still count on the support of Richárd Vörös, but they also soon grew up and began to live independently.

In the surviving documentary heritage of the Vörös family, the changes in the relationship between the different family members is apparent. The letters sent by the husband and wife to each other at the beginning of the century almost exclusively focused on the two common children, Andor (“Bandi”) and Ilona (“Ilonka”). It is typical that the figure of Emma Breitzner only appears in the letters twice before the wedding held at Csákvár: first with regard to getting the papers needed for the wedding (“the death certificate of your deceased wife”), and second, concerning keeping her memory alive (“My letter arrived at a bad time, as I guess, it was right at that afternoon that you were at your wife’s grave with your children”). In the next two decades there is reference neither to her, nor to his former wife living in Viziváros, Mária Popovics, or to his divorce. It seems that this tabooizationand exclusion also extended to the four children Richárd Vörös fathered with Emma Breitzner: by the beginning of the century, only one of them, Tibor, is mentioned in the documents, when after the death of his father he dared to make financial claims against the family.

In letters which the two stepsiblings wrote to their mother, Erzsébet, in the summer of 1913, they speak of Tibor Vörös impetuously. “I was really happy about the joke of little Tibor,” notes Ilonka: “I think the fool will soon be fired from the court of law.” A letter written by her brother five days later details why the family suddenly has to deal with Tibor:

The impudence of Tibor is not a novelty. He was a skunk all his life, and you cannot turn chalk into cheese. Anyway, I am not sure on what grounds he could claim anything here. He received his share of everything in the life of our poor old father, so how could he step forward with all kinds of new claims? It is just as well that he is not demanding a share from the pension. If he comes when I am home, I will throw him out on his ear. Anyway, I remember these rubbish people almost with disgust. He is a filthy hyena and I would prefer a dog carrying the name that I carry, than him.

The analogy of the two letters is not by chance: they both obviously react to the complaints of their mother, each according to their character.

Civil family idyll at the turn of the century. Source: Fortepan

The later fate of Richárd Vörös’ children varied significantly. There is no further news of the “prodigal son,” Tibor, and all we know of Gabriella is that she became a victim of the Spanish flu that swept through the continent in 1918. Elemér, judging by his profession, could not maintain the bourgeois living standards: at his 1908 wedding he was registered as an “electrician” and, a quarter of a century later, as a car driver (of his three known marriages, two ended in divorce). Edit had a similar fate: she married late, in 1926, to a shoemaker’s assistant. She also sustained herself from manual labor: according to the marriage register, she was an embroiderer. In contrast, the son of Erzsébet Mezey, Andor, became a military officer. He was discharged after World War I as a lieutenant, and after his retirement in 1923 he got married, with his profession listed as “clerk”. In 1928 he officially took the “Veöreös-Kovács” name that family members who wanted to emphasize their nobility had already sporadically used before. Erzsébet Mezey’s other child, Ilona, graduated from a training college, and in 1918 married a bank clerk.

It may not be by accident that at the beginning of the century, the nuclear Vörös family only kept connections with the Breitzner children to whom they were not blood related. “Rudi”—Rudolf Redl—occurs in the family letters most frequently, and according to the letters, he may have been a popular figure at family gatherings. The good relationship, apart from the disinterest in financial matters, was supported by a letter of apology he wrote to his upset father in 1894:

If I look back afar to my childhood years, back as long as I can, to the roots of my memories I always see “uncle doctor” who did a lot for me, who always loved me with gentle fatherly love all those years. I remember him with heartfelt concerns at my sickbed, I saw him fighting for my successes and rejoicing over them. He stood above me for twelve long years, always with a warm-hearted smile, rarely with dour expressions, defending-admonishing, but being gentle even if he was upset.

The son, who later Magyarized his name to “Rédei,” was of course more successful than his stepsiblings: he received a doctorate, and in 1905 he got married as the assistant secretary of the crafts chamber of Debrecen. The imperative of the family’s self-interested silence, and intent to forget their past, is probably best represented by the lone funeral monument of Emma Breitzner, which is still to be found in Budapest’s former public cemetery, the Fiume Road National Graveyard.

During the reconstruction of the cemetery in the summer of 1922, her grave was removed, and her remains were unearthed and placed in the arched ossuary built at the beginning of the century. The graveyard’s records do not tell who requested the exhumation and for what purpose. Under the arches, a simple board states: “Richárdné Vörös MD, 1856–1892”. (The birth date is incorrect: it was probably determined based on the date on the death certificate.) Richárd Vörös, who died in 1913, and his third wife Erzsébet Mezey, who passed away the following year, were buried together at the cemetery of Gyömrő, a village close to the capital.

Follow us on Facebook to get notified of new posts!