Blog

In Search of Stepmothers: The Stepfamilies of a Calvinist Minister

Family, autobiography, emotions

Calvinist minister István Miskolci Csulyak (1575–1645) introduced his sixth and final marriage at the age of 65 in his Latin ‘curriculus vitae’ as follows:

‘I was fed up with the home troubles of widowhood, thus I began to consider again procuring the help of a caring wife so that I should be more capable of managing my private and public affairs’.

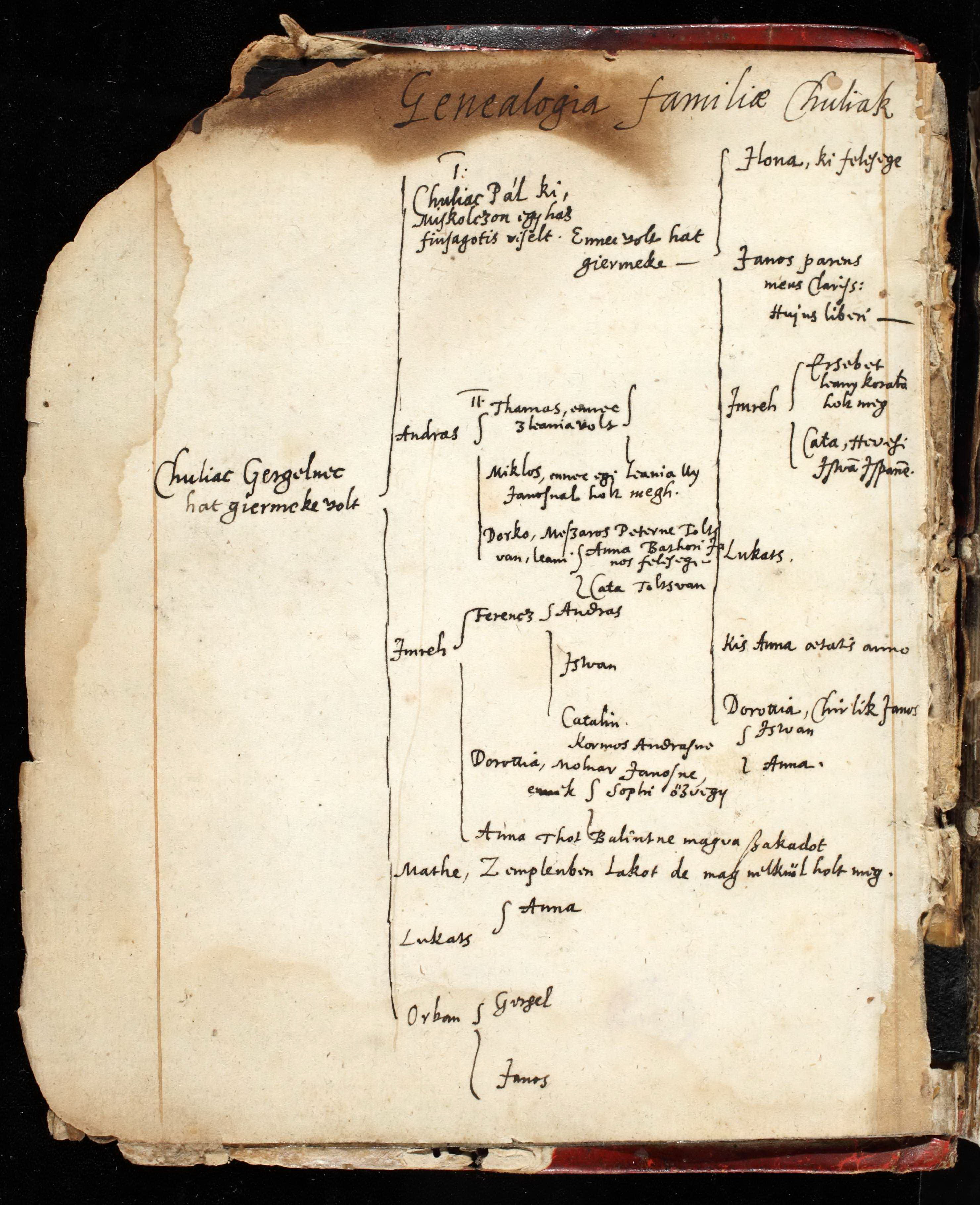

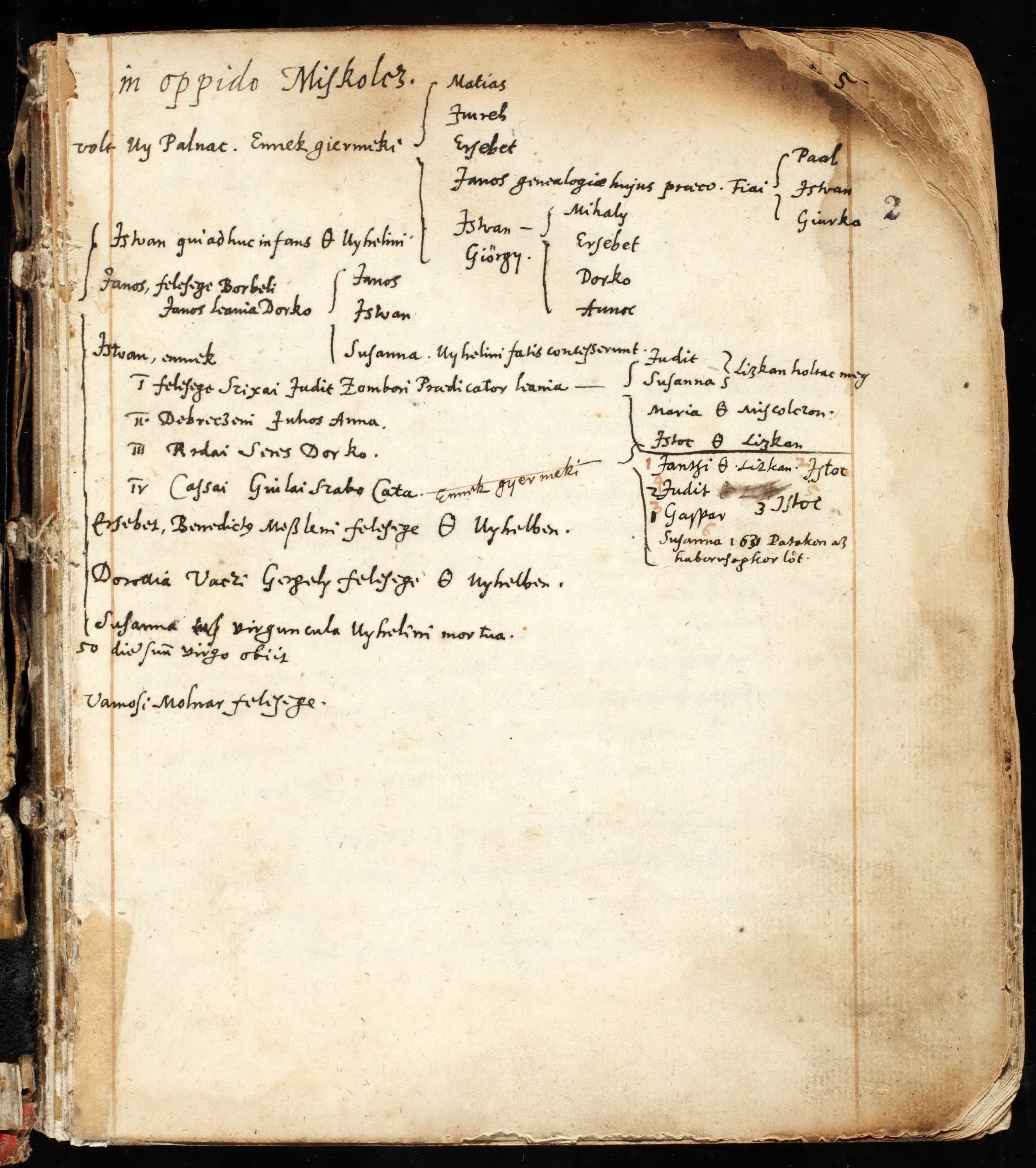

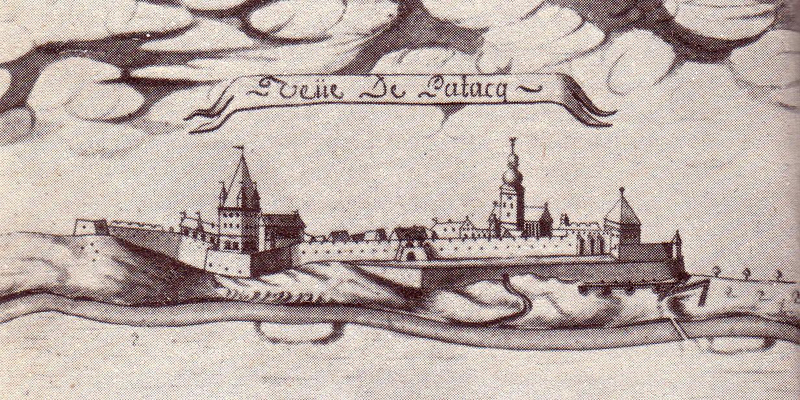

Pastor István Csulyak, as the preacher of Liszka for three decades (1616–45), served the burghers of the wine-growing market towns in northeastern Hungary, a region which changed hands more than once between the Habsburg kings and the Princes of Transylvania in Csulyak’s lifetime. As for his learning, Csulyak learned Latin and Greek in the Reformed town-schools of the region and formed friendships with the late-humanist Calvinist intellectuals at the University of Heidelberg. Csulyak’s manuscript omniarium contains beside his ‘curriculus vitae’ a family tree and a brief family chronicle, some of his correspondence, his occasional poems, his library catalogue and his travel journal.

Historians have recently become increasingly concerned to approach the archive increasingly not simply as a storage site of information but to understand its role in the production of knowledge and the manufacture of social and power relations as well as collective memories. Family archives, from this perspective, can be considered as agents in the formation of family identity and memory. Consequently, the writing and preserving of documents, such as autobiographies, belongs also to the agenda of creating honorable family identities and hiding unwanted ones. Early modern life writers targeted an intimate audience, most typically their children, and the life story represented a tool to preserve some moments in the family memory and to relegate other things to oblivion. Drawing on these insights, we can ask: what kind of images of the stepfamily was it possible for writers to construct and what were the social functions of these narrated stepfamilies within the tradition of these so-called ‘family egodocuments’?

|

|

| Family tree in the pastor’s omniarium | |

The chain of families

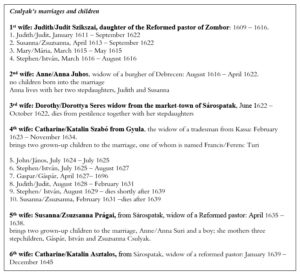

Pastor Csulyak served as the head of consecutive stepfamilies as a result of his six marriages between 1609 and 1639, five remarriages to widows, some of whom were mothers with children of their own. This complex family form, which was created via the remarriage of a widow and a widower whose children mixed as stepbrothers and stepsisters – at this early stage of stepfamily research – seems to have been the most rare stepfamily type in early modern Europe. Widowers tended to choose much younger and never before married brides when they remarried. One obvious exception to this gendered remarriage pattern emerged in regions that embraced some of the Protestant confessions: the widows of Lutheran or Calvinist ministers, who lost with their husbands their home as well, tried to secure the living for their half-orphans by marrying the subsequent local minister or a minister from their acquaintances in the region. Csulyak himself moved in this marriage market and three times married the widows of his minister colleagues, his stepfamily serving as a moral exemplar for the Reformed community.

He first remarried in 1616 as the father of three little children. All his subsequent wives fulfilled the role of stepmother except for the fourth wife, since his children tragically died from plague together with the third wife in 1622. While he thus started a new life with his ‘beloved Katalin’, as he called her, who gave him three children between 1623–34, he also served as a stepfather of her two minor children. We do not know if these half-siblings ever lived under the same roof. Csulyak stepfathered another two sets of children in his fifth marriage (1635–38): an adult girl probably from the first marriage of his wife and another two (he speaks of them in the plural) dependent children from her second marriage, who must have cohabited with their three half-siblings. He did not record what happened to his stepchildren after the decease of their mother(s) nor how the half-siblings and Csulyak himself experienced their probable separation after their shared everyday lives. The Calvinist minister reflected back on all his blended family experiences in the early 1640s soon after entering into his sixth marriage. In his continually reshaped stepfamily with serial wives and his altogether ten children, only one child reached adulthood.

Wives in their stepmother role

Csulyakʼs autobiography suggests that the role of the new wife as stepmother to his small children was an important aspect in his spouse selection. With regard to his consideration of a second marriage, the Calvinist minister commented: ‘I could not remain any longer a widower due to my children and the household’. He had three little children at the time, in 1616, the 5-year-old Judit, Zsuzsanna two-years-younger, and a new-born son, István, having previously buried a baby-daughter. This expectation of care for children and household on the part of remarrying widowers must have been common, since the minister only devoted more words to expressing it when the need was not met. His second wife, Anna Juhos, a widow of a burgher in the town of Debrecen ‘was a real Xantippé [Socrates’s grumbling wife] for me and a real stepmother for my daughters’. The Latin term Csulyak uses—ipsissima noverca—‘real stepmother’ was evocative, and in itself carried negative connotations. Pastor Csulyak added more to his description of this first stepmother when commenting on her death: ‘My two daughters also felt that the stepmother’s love was only on her lips, but that she carried poison in her heart’. Early modern autobiographies and memoirs were not the accepted arenas for the expression of personal feelings. In that manner, Csulyakʼs probable immediate models, his fellow ministers writing diaries and autobiographies, lingered over neither grief nor joy. Csulyak thus continually described the business of remarriage as a strictly practical matter. He remarried each time with exceptional speed, after two or three months of widowhood, social endogamy serving as his wife-selection strategy: all his wives came from the circle of small-town reformed burghersʼ or pastorsʼ widows, relatives and acquaintances, and his colleagues served as mediators in the making of the marriages. Thus, while he briefly depicts his idea of the ideal wife, which matches contemporary stereotypes (obedient, diligent, pious, good housewife), the emotionally laden expectations toward the new wives as stepmothers surfaces in more detail only in his occasional poems. After the painful experiences with the second wife, the stepmother role of the third wife, Dorottya Seres, a widow from Sárospatak, must have become even more crucial.

The Castle of Sárospatak, one of the centers of the Reformation in Hungary, where Csulyak visited some schools and later found some of her wives

Despite this, in the autobiography he lingers again only over the technicalities of his wife selection. We learn from his anxieties from his occasional poem composed for, and probably also performed at the betrothal, in 1622:

Her lips announced, kindly promising

her fidelity, saying:

She will not be a stepmother, a kite [a bird]

who would hollow the eyes of my offsprings

from their head […]

but will be benevolent towards me

and my little ones.

The situation repeated itself when he took his fifth wife in 1635, having again three little children from his fourth wife (his children from the first marriage having already died in 1622), Gáspár, István and Zsuzsanna, aged nine-, seven- and five. In his autobiography, he recorded—as usual in relative detail—the way he was contacted with and briefly courted his fifth wife, Zsuzsanna Prágai, the young widow of one of his colleagues. At the wedding banquet, however, the high expectations vis-à-vis his bride as a stepmother were even dramatized. Singing his father’s wedding poem, Csulyak’s seven-year-old son, István, who was well-trained by both father and school to recite poetry, bemoaned their ʽhelpless orphanhoodʼ, to which the wise elder brother, the nine-year-old Gáspár responded with solace and rebuke: we are not orphans anymore, since we have gained ‘a caring mother’, whom, if she so deserves, we will respect and love as our mother—which is paraphrasing his own words. And he continued:

Seeing our obedience and benevolence towards her

she promised

not to look at us wickedly,

but obliged herself to be as honey,

and not as Medea, that untrue mother

who killed her child

Putting the wicked stepmother on stage in this way at the wedding celebrations must have been driven by very actual fears and anxieties. Csulyakʼs words also reflect that in the seventeenth century the clear cultural contrast between evil stepmothers and loving ʽnaturalʼ mothers was not yet developed: stepmothers tended to be cruel, but ancient stories of heinous mothers were also circulated. Stepmothers could become substitute mothers, but it is emphasized that the emotional bond between stepmother and stepchild was not unconditional.

The Reformed Church and parsonage of Liszka today, where Csulyak served for 30 years

Csulyak’s autobiography scarcely examines the fears and hopes he and his children may have harboured about introducing each new wife into the role of stepmother. Moreover, his life narrative remained totally silent about the children of his wives and himself in the role of stepfather. This omission can be explained by the social function of the autobiography in underpinning the regime of the patrilineal family. From the perspective of the vertical family lineage the lateral step-kindred remained invisible or became non-existent. Csulyakʼs autobiographical narrative was an extended version of the family tree and the family diary, which he also preserved in his omniarium. His subsequent annotations most probably signal the way the family tree and diary functioned as a source for his life-narrative.

Csulyak as a caring father

It did not aim to record the everyday relations within the actual ‘household-family’ such as the presence of stepchildren or other kin and servants, but rather considered each life as a link in the family lineage. In that manner, Csulyak’s eldest son, Gáspár, received the omniarium as his paternal inheritance. The son commemorated the father’s death by publishing the autobiography his father had written in Latin verse, completed by Gáspár with a few lines, and then inserting the published pages into the little manuscript book. In his life-story Csulyak recorded only the dates of birth of his ten children and the circumstances and dates of their deaths, but he used the funeral song, as his contemporaries did, to express his grief and memories of his beloved ones. So we learn from the poem, entitled triste cordolium parentis, written for the death of his first two daughters Judit and Zsuzsanna and his third wife Dorottya Seres, all dying of plague in the autumn of 1622, that he taught them to read and write and they diligently embroidered the poems of their father into house linen.

Similarly, it is only by reading the ministerʼs letters that we learn about the ‘orphans’, as he called his stepchildren, brought by his wives into the marriage and thus we catch a glimpse of him in the role of caring stepfather. His fourth wife, a 28-year old widow, at the time of the marriage in 1623 was ‘the mother already of two children’, as he characterized her briefly in the autobiography. In letter from 1630, Csulyak humbly begs the pardon of the aristocratic patron of his already adolescent stepson, Ferenc Turi. The stepson was detained in the castle of Ecsed about 70 miles from his stepfather’s home. Csulyak’s intervention makes it obvious that he knew the boy well and devotedly provided for him:

[Ferenc] must be a quick and loyal apprentice, since I never found him in any fault, but since he is young and his brain, like wax, bends easily if exposed to warmth, I request Your Lordship to educate him under firm discipline so that he should be able to fear even as an old man. If my praying in front of Your Lordship for my son will be considered [. . .] my presently sad face will become cheerful.

Csulyak sent a copy of this emotionally rich letter to his stepson, a half-brother to his own three children with Katalin, Ferenc’s mother. Thus the letter and its copy provide evidence of their close relationship, perhaps dating back to their earlier co-residence, because Csulyak had already been was married to Ferenc’s mother for seven years. Csulyak identified with the boy (‘I am ashamed for him’), whom he called either his ‘son’ or ‘stepson’, while also conjured ‘the night and day lamentation of his mother’. Even if we cannot say with certainty whether the boy, who was a merchant’s son, could thank his stepfather for his good fortune, in obtaining the patronage of István Bethlen, the ‘little count’, the nephew and designated successor of the Prince of Transylvania, but Csulyak obviously was ready to support his stepson even in this embarrassing situation.

István Bethlen (1606-1632), the Captain of Várad/Oradea

The minister continued to provide all the support he could to his new stepchildren through his fifth wife and marriage. During its four years between 1635 and 1638, he had a grown-up stepdaughter, for whom he composed a wedding song and whose wedding banquet he attended, but he also had in his own household dependent stepchildren—the children of his current wife probably from her second marriage—living with him. The old stepfather, already in his sixties, tried to provide for the future of the ‘little orphans’ of his wife by soliciting in yet more letters both the Prince and the Princess of Transylvania in their capacities as local landlords, to lend their support to his spouse in buying a house in the town of Sárospatak, where she could live with her children following his own death. The elderly pastor thus had at the time at least five underage children in his house: three children born from his ‘charissima Catharina’, his fourth wife, and the children of his actual wife, Zsuzsanna, from her previous marriage. Yet again, his much younger wife died first and thus his lines explaining his sixth marriage about the management of his ‘private affairs’ as the reason for his remarriage, which served to introduce the chapter, probably meant his three children. His little stepchildren, in accordance with the legal regime and the usual practice at the time, may have been taken in custody by their blood relatives as their guardians. We are left to sheer speculation with regard to how the separation of the two sets of children, the four half-siblings after four years of cohabitation might have affected them emotionally.

The six-times married Calvinist minister resolutely provided for his stepchildren, although we know nothing about whether and how these relationships were maintained when the biological mothers of his stepchildren died. Nevertheless, stepparents need to be acknowledged for the important roles they played, along with other figures such as older siblings, half-siblings, godparents and foster parents for example, in the early modern shared enterprise of parenting, even if a stepparent’s role, as of others, was limited to certain life-cycles of the family and of its individual members. Paradoxically, the concept of family lineage excluded the children of pastor Csulyak’s wives’ previous marriages. Csulyak’s stepchildren are excluded from his life narrative in favor of a representation of a simple patrilineal family even though his heirs had little else to inherit than his writings. The early modern horizontal kinship ties through stepfamilies might be stronger than the written legacy influenced by the regime of patrilineality would have us believe.

Follow us on Facebook to get notified of new posts!