Blog

“Such a numerous family as mine”. István Széchenyi as Stepfather

Zoltán Fónagy presents one of the best-known Hungarian historical figures in a lesser-known role.

István Széchenyi, sometimes referred to as “the greatest Hungarian,” was a key figure in the modernization of nineteenth-century Hungary. He was the formulator of the first modernization program, and contributed to civic transformation through his highly influential books, his enthusiastic organizational work, and significant financial sacrifice. The foundation of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and the building of the first bridge at Pest-Buda, the Chain Bridge, are associated with his name. As an initiator, he played a role in the regulation of the Danube and Tisza rivers, introduced steamboats to Hungary, and founded the manufacturing industry.

A “dream couple” from the Hungarian Reform Era: Count István Széchenyi with his wife in national dress in a literary fashion magazine (1843)

After almost a decade of platonic adoration, Széchenyi married Countess Crescence Seilern at the beginning of 1836. The thirty-four-year old Hussar captain fell in love with the twenty-five-year-old countess around 1824–25, and after a long period of seeking his true calling, it was then that he decided to devote his life to public affairs. The existing Széchenyi biographies usually associate the two events by emphasizing the inspiring role Crescence played in her husband’s great deeds.

The Romantic open secret

In the period of the formation of their love, Crescence was married to Count Károly Zichy, President of the Chamber and more than twenty years her senior. She was also the mother of three small children. Although she felt flattered by the affection of Széchenyi, and moreover she soon became emotionally involved with him, Crescence did not engage in the “usual” role of a mistress. More than a decade passed with the two meeting and exchanging letters periodically in a mannered style. Széchenyi, according to the regulated nature of social life, even had free entrance to the home of the Zichy family. The relationship of the admirer and the husband was so “civilized” that—as is clear from Széchenyi’s diary—sometimes they would attend to Crescence together when she was sick, or even in labor. During this decade of platonic love, the countess gave birth to four further children by her husband. With the infant mortality rates of the period, it is extraordinary that all seven of the couple’s children reached adulthood.

|

|

| F. G. Waldmüller: Countless Crescence Seilern , 1828. | Count Károly Zichy |

When Károly Zichy suddenly died in 1834, at the age of fifty-five, he was not only mourned by the seven adolescent children, as Crescence was already his third wife. The first marriage was the shortest; Countess Franciska Esterházy died at the age of twenty during her second childbirth, in which her baby also passed away. His second wife, Countess Júlia Festetich—who, incidentally, was Széchenyi’s cousin—bore eight children in eight years, amongst them twins, and only one of whom died in childhood. Júlia died at the age of twenty-six, after giving birth to her last child. Three years later, when the twice-widowed count married the twenty-year-old Crescence, the bride received as a “wedding gift” eight stepchildren: a seventeen-year-old boy from the first marriage, and seven children aged between three and eleven from her husband’s second marriage.

The stepfamily of Széchenyi

On February 4, 1836, after the year of mourning was over and István Széchenyi could finally bring his new bride to the altar at the Krisztinaváros (Christinenstadt) parish church, he immediately became the head of a family with children from three different marriage beds. He had not only paternal responsibilities for Crescence’s seven children, but also for his new wife’s stepchildren, the children from Zichy’s second marriage (the youngest of whom was nineteen at the time of the wedding), who often stayed in the new household of their stepmother. Their feeling of being at home was certainly facilitated by the fact that their birth mother was one of Széchenyi’s cousins.

The blended family was further complicated by the birth of the couple’s two common children, Béla and Ödön. The third child, Júlia, died when she was two weeks old; she was the tenth and only lost child of the then forty-four-year-old Crescence.

A number of biographies find it worth noting that Széchenyi behaved as a responsible paterfamilias for the Zichy children. In the language of social sciences, Széchenyi accommodated well to the contemporary norms and conventions connected to the role of a stepfather. The exceptionally good source situation, including an abundance of ego-documents (constantly written diaries and an extensive family correspondence) make it possible also to uncover the “emotional network” behind the public positions.

In his biography of Széchenyi, László Csorba characterizes the count’s pedagogical standpoint towards his stepchildren as “purposeful efficiency,” the same type that made his enterprises so successful (horse racing, the National Casino, the Academy of Sciences, the Chain Bridge, steam mills, river regulation, etc.). This efficiency is most clearly reflected in the way he represented the financial interests and career choices of the Zichy orphans, while keeping the boys on track. He negotiated in the Viennese offices that as the orphans of a deceased leading official, the children would receive financial support from the state until they were adults. (This was a royal grant and not a natural right at the time.) The main inheritance of the fifteen Zichy children, the estate complex of Lébényszentmiklós, was handled by the two eldest sons, Pál and Henrik, after the death of their father. As the estate did not bring in much income, after a few years the boys got fed up with the burden of farming. The sale of the property was handled by Széchenyi and it was he who found a solvent buyer in the person of a Viennese banker, Count György Sina, the main financer of the Chain Bridge project. He also kept the shares of Crescence’s children in low-risk investments until their adulthood.

The learning of the role

The fact that Széchenyi had free entrance to the Zichy household during the latter’s life, meaning that the children were not unknown to him, may have eased him into “finding” his role as a stepfather. He knew the smaller children since they were born. He was present at their home exams (aristocratic children sometimes had to give testimony of what they had learned from their private instructors in front of family and friends) of the eldest son, the eleven-year old Alfréd; he heard the ten-year-old Karolina—whom he had sent a cutting as a birthday present—crying with stage-fright when she was asked to play the piano; he knew when the children were sick. After the death of Zichy he consciously prepared to be a stepfather with his typical perfectionism. For instance, in June 1835, in the middle of the year of mourning, he made a list of the names and birthdays of Crescence’s seven children!

In the next twelve years, “meine Waisen” (“my orphans”) became frequent characters of his letters. He referred to the Zichy children mostly with the phrase, “my beloved but stepson/stepdaughter.” In the letters dating after the wedding he mentions his new role a number of times, showing an acute awareness of his fundamentally transformed circumstances. From these notes, one can simultaneously sense his anxiety, but also a degree of nervous excitement.

Immediately after the wedding he had to face a problem with his house; the Pest home of the forty-five-year old bachelor—even if it was furnished with aristocratic eminence—did not fit a family with seven small children (and another ten “visiting” grown-up children) and their attendant personnel.

“I married the widow of Károly Zichy some days ago, so I am the head of a family with numerous members. A thousand joys accompany my life, but there are also many problems coming with that. I was not able to acquire an apartment yet, and I am indeed most embarrassed about that right now”

– he wrote to one of his friends whose house seemed to fit the needs of the big family. Finally, however, he rented out the second floor of the Ullmann Palace at the Rakpiac close to his previous home, which became the Pest home to his populous household until he suffered a mental breakdown in September 1848.

Father to the boys

Széchenyi was heavily involved in the upbringing of his stepchildren, especially that of the four boys, as according to the norms of the period, boys over the age of infancy (ca. above six years old) were typically raised by their father. Even in the midst of his countless public duties he had an eye on their physical and intellectual development. During his longer absences he sent instructions to the teacher of the two older boys, Alfréd and Géza, at regular intervals, also asking for detailed and honest reports on their progress.

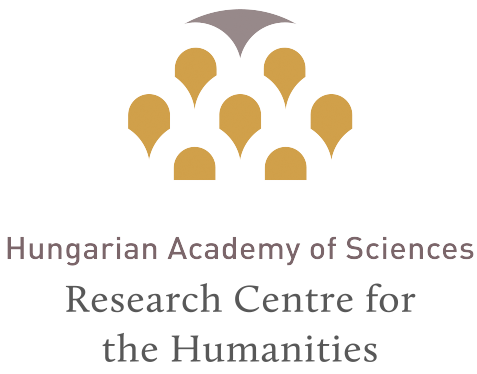

The swimming pool on the Danube close to the home of the Széchenyi family

He evidently used his social capital in order to provide his stepsons with a smooth beginning to their adult lives, or at least the best possible “starting position.” He arranged for the eldest son, Alfréd, who studied law, to do his practice with the personalis judge (the president of the royal court of law) and to take his exams at the earliest possible date. He attended to the acquisition of new clothes required by the new situations (e.g. the black Atilla, a braided Hungarian shell jacket worn by law students) or to the organization of the nineteen-year-old youngster’s trip to Pozsony.

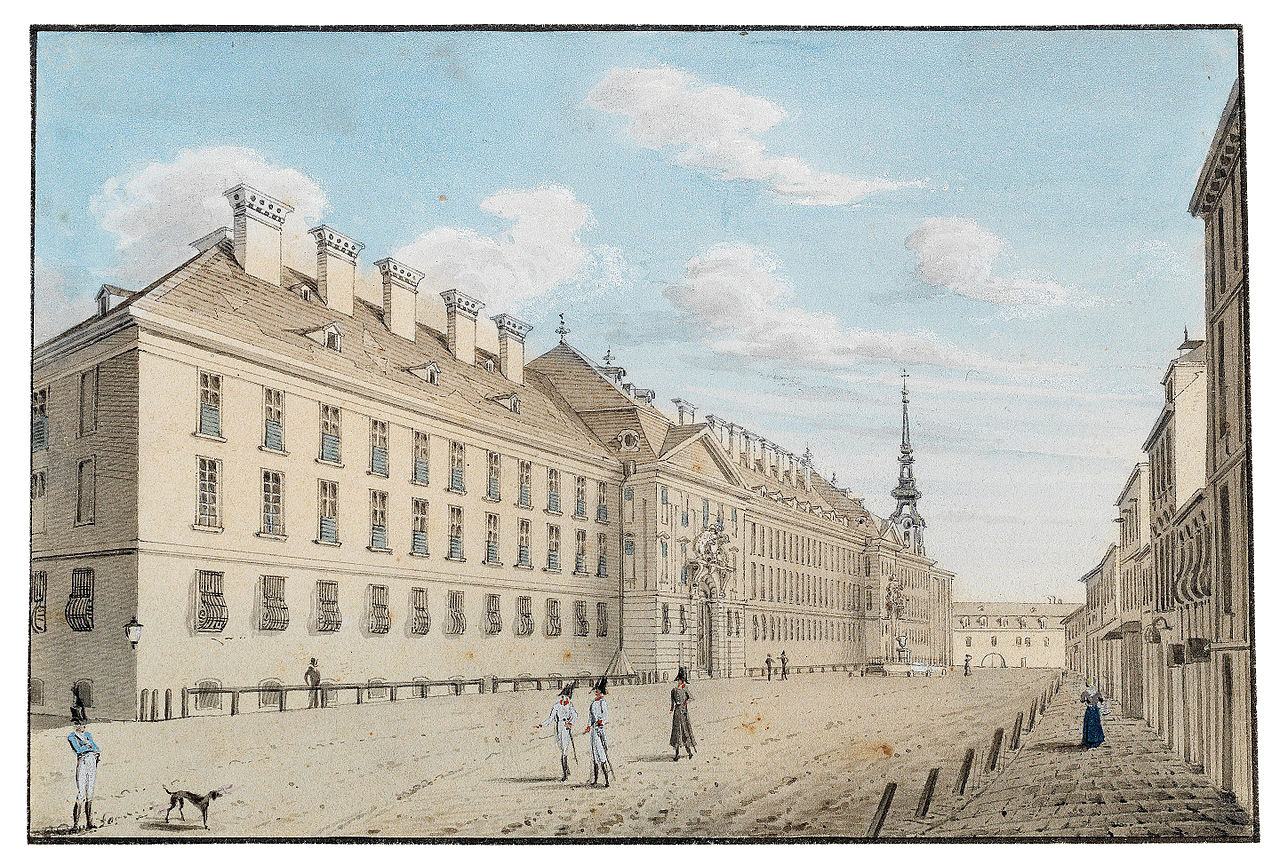

The two younger boys were referred to much less in Széchenyi’s diary and letters. At the beginning he did not have many fatherly duties with the younger boys, who were three and five when he married, and when they became teenagers he sent them to the academy of military engineering in Vienna in order to safeguard their future livelihood, despite the moderate inheritance from their father. In choosing their career, the strong technological interest and civilian visions of Széchenyi must have played a significant role, as the knowledge they acquired there also seemed to be very useful in a civil profession.

It seems that his fatherly hopes were fulfilled, as by the late 1850s the boys appear in the letters as younger military officers who were on “the right track.” “Quel excellent garçon” [What an excellent boy!], rejoiced Széchenyi at Döbling over a letter he received from the younger son, Rudolf.

The building of the military engineering academy in Vienna, the Stiftskaserne

Alfréd, the black sheep

Regarding the character of Alfréd—who became his stepson as a fifteen-year-old adolescent—Széchenyi had concerns from the very beginning which later, when the young man became independent, were proven to be justified. The problems described about the nineteen-year-old law clerk still partly sound like the complaints of a parent about a negligent and weak student: “He is pretentious and lazy. His writing is especially weak, both his style and his orthography. He has to progress in that.” The fear of his total failure in parenting already arose in him back then: “I am very much afraid he will turn out to be a nobody. He writes nothing else to his sister [about his legal internship in Pozsony] except how much fun he had, and what further good times he is looking forward to.”

There is little direct information on the young man who left his family home in the middle of the 1840s, but the negative intuitions of his stepfather were confirmed. Alfréd was increasingly gripped by a gambling addiction. News came to the family home—sometimes from Vienna, sometimes from Pest—about his gambling losses, which were colossal in comparison to his modest fatherly inheritance. Széchenyi took the parental role seriously: although no formal legal bounds connected him to the young man, he could not behave indifferently towards Alfréd’s gambling addiction. His emotional involvement was all the greater given the fact that Crescence, as a mother, was deeply saddened by this potentially fatal addiction of her son. Although in his diary he noted his regret that when they met he was tough and stern with Alfréd, he still could only write his name accompanied by negative words (beau, crazy, fool, man of pleasure, dandy). He was upset and saddened by the fact that Alfréd still had no goals in life: “He will end sadly—and he depends on me,” Széchenyi lamented at the beginning of 1845. Despite his hopelessness after hearing of a loss of one major sum or another, he kept trying to push the young man back in the right direction.

Of course, the rational fatherly advice did not bring about a turning point in the lifestyle of the addicted young man. Széchenyi registered the news in his diary in the beginning of 1848 that Alfréd “again lost some twelve or fifteen thousand florins in Vienna. He will have barely anything left.”

In the vast collection of Széchenyi family sources, only an obituary notice tells of the ultimate fate of the “prodigal son”: he died in Cairo on January 7, 1856. Of the “seven stepchildren”, he was the only one not to outlive his mother and foster father.

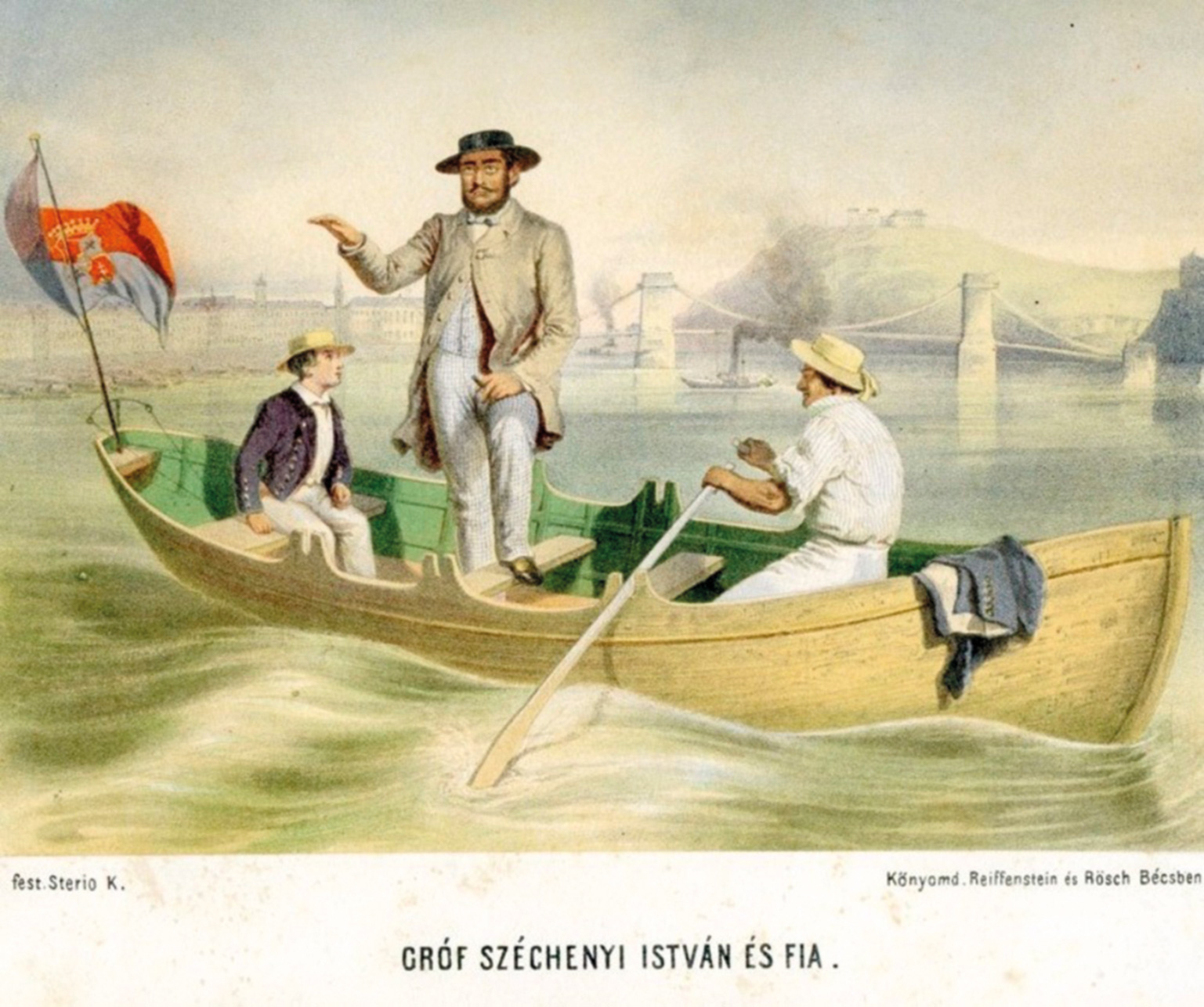

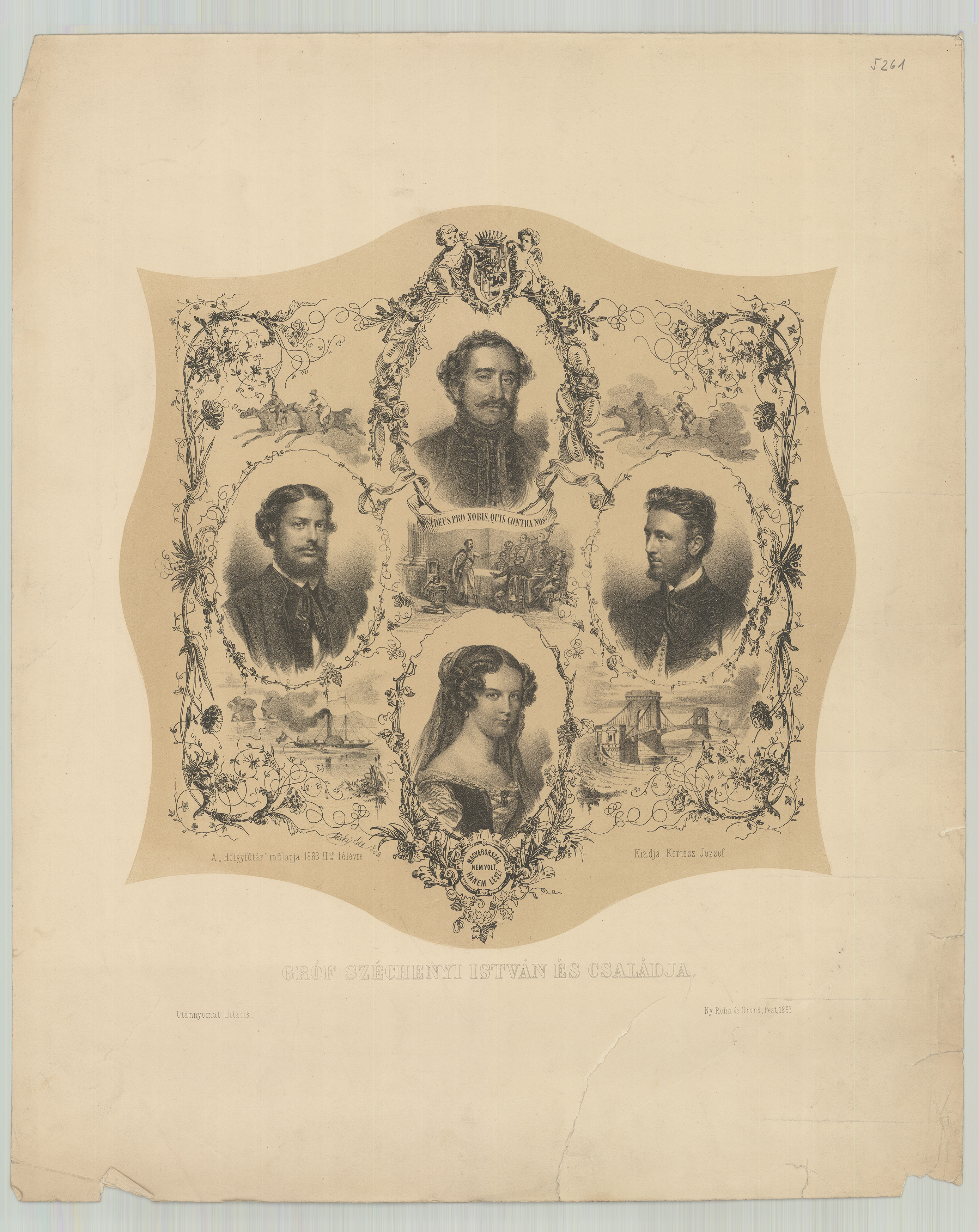

On the “official” picture of the family, apart from the parents only their two shared sons, Béla and Ödön, were preserved by future memory

Géza, the late bloomer

When smoothing the way for Géza’s future, the conscientious father had to face different problems than in the case of the playboy, Alfréd. He was almost always referred to by Széchenyi as a “good boy, worthy of love”; however, with regard to his endurance, diligence, his sense of purpose, and his intellectual capacities, he was mostly discontent. In a letter from Döbling, he described the then almost thirty-year-old young man as “this hearty boy, filled with the most noble sentiments; however, he always finds himself amongst those of whom they say: always missing the target!”

Although Széchenyi’s diary occasionally contained a note of disappointment, through his career twists Géza could always rely on the support of his influential foster father. When he was a child he was attracted to the sea, so Széchenyi enrolled him at the naval academy in Venice to get officer training. In order to prepare for this, he instructed his secretary, Tasner, from Pozsony, that the twelve-year-old “Géza should immediately start learning the Italian language. Counting, calligraphy, religion, and the Italian language are the things he has to know to be admitted to the academy at Venice.”

After four years he had to be excused from the “navy school” as “the boy is a bit short-sighted, so his career improvement is rather doubtful.” For the next decade—with occasional interruptions—Géza pursued a military career. Széchenyi, using his connections at the highest levels, tried to give his stepson a helping hand. For instance, he arranged his promotion to lieutenant at the head of the Imperial War Council.

His fatherly care, however, was not limited to boosting his career. In their meetings and through their letters he tried to develop the characteristics he believed were desirable (a sense of purpose, constant self-reflection, sparing civilians, etc.) in the boy who had left his mother’s home when he was twelve. It was no different towards the end of his life: it is testament to the emotional connection of the two persons that the thirty-year-old Hussar captain, despite the constant “vexing,” gladly and frequently spent time with his foster father at the sanatorium in Döbling. Széchenyi, who was a maximalist about the people around him, felt love, compassion and anger towards the young man. He shared his thoughts and concerns with his son Béla in 1857, and to some extent left his nine years older half-brother in his guardianship:

“his biggest problem—between you and me—is that he is somewhat short-witted! I have never seen anyone who wasted more money, time and health than he did … But apart from that he is a righteous, clear, honest and grateful boy. So please, I beg you, don’t leave him on his own—as he has a hard time keeping his equilibrium when I am not around anymore!”

In the last two years of Széchenyi’s life, he finally really communed with his closest stepson. Having left the army at the age of thirty, Géza essentially became his father’s secretary while he was living a reclusive life in Döbling. Széchenyi, for his part, looked upon Géza’s “settling down” with pleasure and fatherly pride.

The private sanatorium of Döbling: István Széchenyi spent the last eleven and a half years of his life in the suite at the left corner of its first floor

Father to the girls

According to the contemporary gendered parental roles, the father had few duties in the nurturing of girls. As stepfather to his three foster daughters, Széchenyi also saw his most important task as providing financial security: for instance, handling their father’s inheritance, financing their upbringing, and maintaining the social prestige of the family, ensuring a marriage that fitted their status.

Of the three stepdaughters, the eldest, Karolin, spent six years in the household of her foster father. She was married to Count Dénes Festetich, at the age of twenty-two, and her choice was most welcomed by Széchenyi. He connected the happiness in his private life with one of the most important moments of his life’s work. In a letter to the designer of the Chain Bridge, W. T. Clark, in the spring of 1842, he stated that “my wish is to settle the day of the wedding close to August 20, so at the same time as the laying of the bridge’s foundation stone, the foundation stone of my grandfatherhood would also find its place.”

The ceremonial farewell letter which Széchenyi addressed to Karolin demonstrates how the social expectations of the stepfather role were filled with emotion during his nurturing, caring for, and living together with his stepdaughter:

“My dear Karolin!

When the almighty Lord took your father, by the bond created between me and your honorable mother, I took the great and holy duty given by providence that you became my daughter. Whether I managed, among the numerous and diverse duties I had, to substitute your father’s role I am not sure. But I assure you, and call the heavens as a witness, that I always turned to you with fatherly love, and constantly tried to develop all the noble and beauty that is in a woman as much as I could.

Preserve all the lessons with which your mother tried to bring you up as a good daughter and taught you to be a loving wife… Never forget about our common homeland, and believe firmly that without affection and love of the homeland and the fellow citizens, the noble public spirit would never be realized, and only that enables us to raise our homeland from its present, highly subordinate status.

Be blessed by the almighty Lord; be protected and sheltered in every one of your moves!

Your fondly loving father,

Your István Széchenyi”

The fondest connection, however, formed towards the second daughter, Mária. When Széchenyi married, Mária was fourteen, in poor health for years, and sometimes in a critical condition. Her foster father, while emotionally supporting Crescence in this difficult situation, also experienced his own fatherly worries. He even recurrently brought up his concerns about Mária in his letters on public affairs. As he wrote to Ferenc Deák in 1840: “great trouble has visited me since we last saw each other. Mária, my most beloved daughter, is very sick. We believe she is close to the end.”

Upon entering her twenties, the most beloved stepdaughter not only regained her health, but also started to “bloom” as a woman. The stepfather proudly registered Mária’s beauty in his diary a number of times. As he noted after a ball in 1844, “Marie war sehr hübsch” [Marie was really beautiful]. In these years the daughter frequently filled in for her ailing mother in public appearances: she appeared at the side of her stepfather at parties, in theater lodges or on strolls in the Városliget (City Park). Mária married Count Antal Wenckheim in 1851, during Széchenyi’s darkest years at Döbling, who after the “clearing up” of his mind accepted the new family member not only without reservation, but with expressed happiness.

The letter sent from Döbling during Széchenyi’s final summer illustrates his warm emotional connection to Mária, perhaps further fostered by the concerns about her health when she was young:

“My dear gently loved Mária!

Your dear letter touched me very much and filled me with real joy! You know that I always felt such an affection for you, that there was a serious threat that I would have behaved unjustly with your siblings! You are still my heartthrob and you cannot believe how much relief it is to my broken heart, yes, at least for some moments it fills me with joy and pleasure to see you at the side of dear good Tóni, surrounded by your blooming children and thinking back to the days when you made us worry so many times, and we only had the slightest hope of ever seeing you healthy and active.”

Much like the two younger boys, the youngest Zichy girl, Ilona or Helene, left less trace in the private documents. She only lived in Széchenyi’s home as a young girl; by 1846, she already lived in an elegant boarding school in Vienna. The few references which appear in the Széchenyi letters talk of a harmonious, warm parent–child relationship. During his short visit to Vienna as the government official organizing financing for the regulation of the Tisza, he admits that he would rather “have pressed my little Helene to my breast: I would have certainly appreciated it more than the discussions with financers.” As the old count shared the news with his wife from Döbling with pleasure: “Helene wrote a really kind letter. Hug her in my name.”

As for what sort of stepfather the children considered the “greatest Hungarian” to be, we can largely only assume based on indirect signs. Nevertheless, if we consider the frequent visits and letters from the Zichy boys and girls, then we can assume that the love and warmth was mutual. Széchenyi in his role as a stepfather can also be characterized by his typical perfectionism and sense of duty. These fragments of complex emotional connections between foster father and children are in contradiction with the persisting image of Széchenyi, the aristocrat reformer as a “man of reason” who only saw people with whom he communicated as utilizable resources.

Follow us on Facebook to get notified of new posts!