Blog

“While old people seek vice, maidens look at the pockets”: widows and their chosen ones

This post by Eszter Baros-Gyimóthy provides a vibrant, vivid image of the fragility of family in traditional societies, using eighteenth-century church registers of Štitnik (formerly Csetnek), today in the middle of Slovakia.

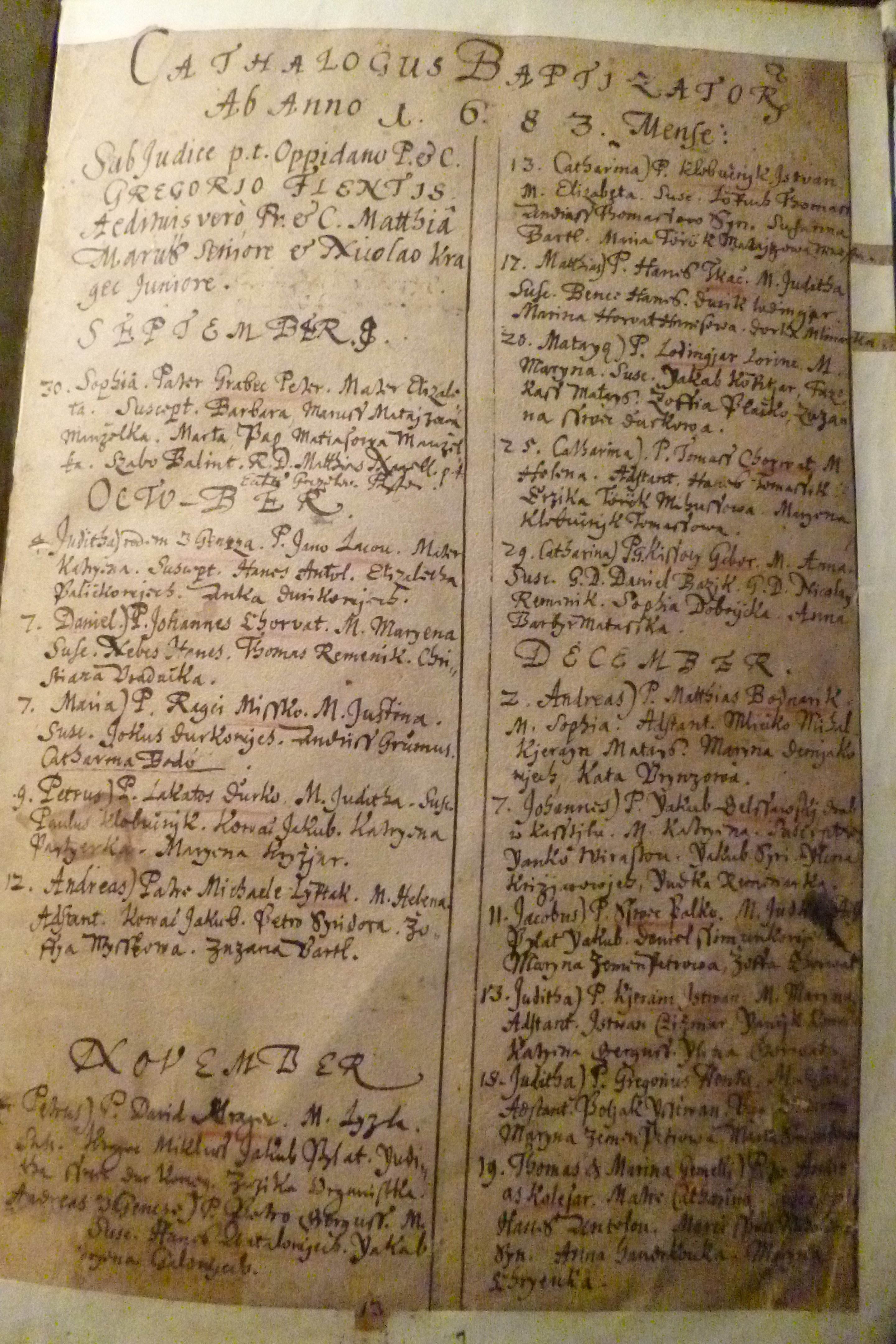

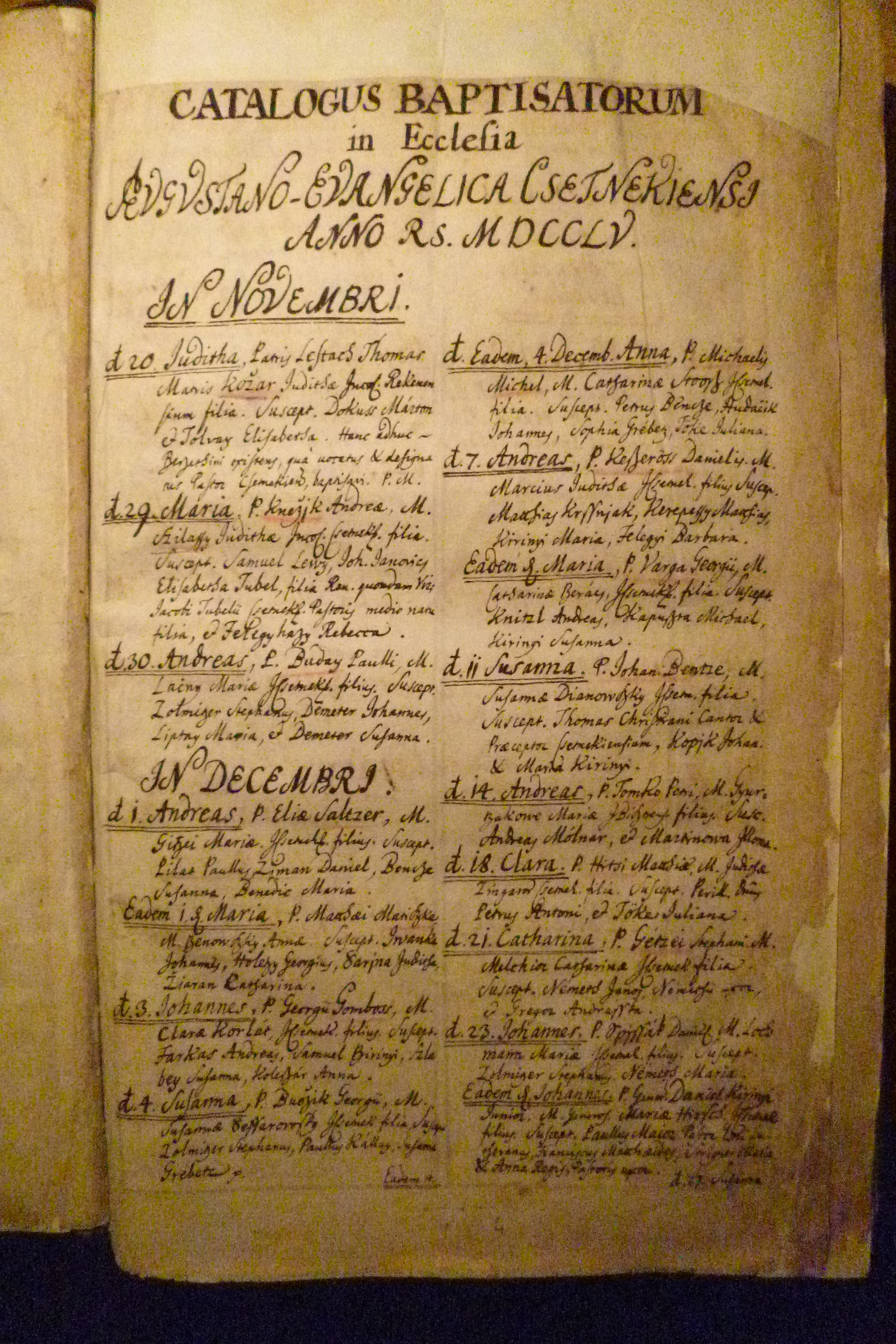

Much like today, the past also saw a general desire for women and men to live in a relationship. Until recently, the natural order of life was that this desire was fulfilled by a marriage. The eighteenth-century Lutheran and Catholic church registers of Csetnek, in historical Gömör County, further reaffirm this.

Widows at the crossroads

In an ideal case, a marriage provided emotional, financial, and social stability for both parties—albeit a stability determined by both parties’ gender roles. However, due to the high mortality rates of our ancestors, one had to accept widowhood as a natural part of life. The death of a spouse or parent fundamentally changed the everyday life of a family: the surviving widows had to learn new ways to find their own well-being as well as that of their children.

After the death of a spouse, the widow or widower could choose from a number of opportunities. They could decide not to remarry: in such cases, a widow would keep using the name of her husband and could manage his possessions. She became the head of the household, but in economic matters could ask for the help of a man from the family. Alternatively, the widow could substitute the lost partner with a new marriage. In this case her own children, possibly those of the spouse, and their common children formed a mosaic family. Someone widowed at an old age could give up her own household and move in with one of her children, where she could help out in the home and with bringing up the children.

Of course, the intent of a widow was not the only issue in remarrying. The chance of a new marriage was influenced by a number of factors, such as sex, age, financial situation, whether the person who entered the “marriage market” had a child, if so then how old, and so on. The pressure of bringing up an underage child usually pushed widows towards remarrying, while having older cohabiting children typically encouraged the widow to retain her independence. A child could worsen the chances of a widow remarrying, as a stepchild—from the point of view of the man—could endanger the inheritance of goods in a family.

Jan Frans van Dueven: Medici Anna as a mourning widow (1717)

Jan Frans van Dueven: Medici Anna as a mourning widow (1717)

Csetnek and its inhabitants

Situated west of Kassa, the town became well known for the mining and processing of its good-quality iron ore. In the eighteenth century it was inhabited by both Catholics and Protestants. Both confessions had their own church in the town, to which a total of eleven filial churches in the surroundings of the town belonged. The Lutheran church registers survive from 1684 onwards, while the data of the Catholics were registered by the local parish priest in the reawakening community, starting in 1735.

In the period of the census ordered by Joseph II in 1787, a total of 2,011 people lived in the town. 15 percent of the men who lived in the town were noble, though they owned very little land. The proportion of craftsmen and merchants amongst the burghers was high, while peasants lived in the surrounding villages. According to the contemporary ecclesiastical records, the number of Lutherans was around 2,400, while that of the Catholics was likely between 1,000 and 1,200.

The marriages were mostly tied here

The marriages were mostly tied here

Csetnek’s Evangelical Church built in the 14th century

The changes of remarrying

In the villages of the parish of Csetnek, the ratio of remarrying was high: in the eighteenth century, one of the marrying parties was a widow or widower at approximately one in three weddings. In Csetnek—as in the period in general—men remarried more frequently than women. Aside from the decade that followed the outbreak of plague in the 1710s, widows were less successful at the marriage market than widowers. Remarrying twice or three times was not uncommon, but there were “record holders” in both sexes. The Lutheran Judit Kalay and Katalin Németh both married four times, as did the Catholic István Gracza; however, the Lutheran István Getzeg married no fewer than five times!

The more favorable condition of men reveals itself in a number of fields. Not only could they remarry more frequently, but also more rapidly. Even at an advanced age they had a better chance of finding a spouse who usually was younger, and not necessarily widowed herself.

80 percent of men who were widowed before the age of forty remarried, but men in their forties also found ways to start a new family in 50 percent of cases. Of course, there were also those who died shortly after their spouse, not having time to remarry. For instance, the Catholic János Zoller buried his wife on September 10, 1806, and on October 29, his name was also introduced to the necrology: indeed, the parish priest introduced the one-and-a-half month earlier widowed man as “groom”!

Men widowed in their fifties mostly lived their remaining years relying on their children; nonetheless, 30 percent of them still remarried. For instance, the nobleman János Csiszár led his second wife, Anna Czigler, to the altar at the age of 70, while another nobleman, György Feledházy, stated he was 79 when he married a widow, the 48-year-old Anna Benedicty.

For women, the chance of remarrying decreased more rapidly and more radically. Brides widowed in their twenties remarried in two-thirds of cases, and half of those widowed in their thirties also remarried. However, women who were widowed in their forties had only a 15 percent chance of finding a new husband.

Widowed woman with her child and couple with their newborn in the City hall of the Göttingen

Those who remained widows

Nor was it uncommon that spouses, even if they were of a fertile age, chose to remain widows after the death of their husband or wife if they did not need a new marriage to survive. Women may have been attracted to the fact that, as widows, they had a level of authority over their children and their possessions which they could not have dreamed of as wives. Some examples of long widowhoods lasting until death:

The Catholic János Lendaczky buried his wife at the age of 37 and was a widower for 21 years. The Lutheran János Kompanik lived without a wife for 25 years after he had become a widower when he was 39. Eszter Bodó lost her husband, the nobleman Jakab Lány, when she was 32, and lived as a widow for 28 years. Her younger sister, who was married to Sámuel Lány, buried her husband when she was 29 and lived for a further 26 years.

After the death of the Emperor Francis I (1765) Maria Theresa appeared only in mourning clothes in public.

The painting by Anton von Maron, around 1772

The length of the grieving period

The length of time it took to remarry after losing a spouse could significantly vary. Lutheran men at Csetnek usually kept the “grief year” while their Catholic counterparts only lived without a wife for an average of nine months. By contrast, Lutheran women were widowed for an average of 2.6 years, and Catholics for an average of 3.4 years. Widowed women only had a good position on the marriage market after the plague of 1710. In the following decade widowed women were on average “sold” within a year.

It is no surprise that young people remarried most quickly. Two-thirds of men who lost their wives before the age of 35 founded a new family within a year. As taking care of small children and supplying the household was entirely alien to the roles attributed to men at the time, remarrying quickly was a necessity. Substituting the role of mother and wife was especially important if there was no older female child or relative who could—at least temporarily—take over these duties. When the Lutheran Mária Szpisak died on July 9, 1777, before she turned twenty, her husband Mihály Majoros and an eight-month-old child mourned her. The father brought the widow Mária Galló, who undoubtedly was a great help in taking care of the young child, to the altar on August 5, a mere 27 days (!) later.

The altar of the Protestant Church in Csetnek

Fendi Peter: The poor officer’s widow (1836)

Widowers and maidens

István Gracza, a Csetnek brewer, married four times. His first marriage was at the age of 27, which was somewhat late for the period. He had a marked preference for maidens between 20 and 25. At his last marriage, the then 69-year-old man brought Mária Kolisch, 34 years younger than him, to the altar. After his first two marriages, Gracza was left widowed with two children under 10, which explains why he always brought a new wife to the house within two to four months.

István Gracza’s choice can be considered typical: Lutheran widowers—irrespective of their age—preferred maidens as their new wives. Of course, this frequently led to a large age gap between the spouses. In January 1736, a nobleman, the 61-year-old widower Jakab Tubel, married the 18-year-old noble maiden, Erzsébet Umbehauenn.

The majority of Csetnek’s Lutheran widows wedded widowers. However, in rare cases, widows would marry younger men, sometimes 15 or 20 years younger their junior. Marina Belicza, a widow over 50, married the celibate András Ziman, who was almost 24 years younger than her. The widow did not have an orphan from her first husband, nor did she have a child from her second marriage. In 1792 the 40-year-old Lutheran widow, Zsuzsanna Hartman, appeared in front of a Catholic altar to marry 22-year-old Mihály Kánya.

Catholic widows married younger men less frequently, and the age gap between the spouses was also smaller. Lutheran church authorities kept forbidding marriages with significant age gaps, as “these marriages carry in themselves the hopelessness to give birth to a child.” These marriages furthermore left many orphans, who became burdens to the congregation. In many cases, marital discord was also attributed to the big age gap.

The young woman grabs the old man’s purse, his eyes are obscured by the erotic desire.

The young woman grabs the old man’s purse, his eyes are obscured by the erotic desire.

Hans Baldung Grien: Unequal marriage (1507)

Libertine widows

Every family had to cope with high infant and child mortality rates; as such, widows only brought an average of one or two children to the mosaic families. As widows had typically already given birth, they were proved to be fertile: the same was also true for majority of husbands. It was not by chance, therefore, that on average less time passed between the births of the first common children after remarrying than in the case of those who were starting their first families.

Women and men who had previously been married probably had a more “libertine” relation to pre- and extramarital sexual life than maidens and celibates. In baptismal registers, next to the names of illegitimate children, one often finds that their mother was “relicta vidua” (surviving widow). If the parents later got married, the child was legitimized by the marriage. In the church registers, this was indicated by crossing out the qualifier “spurius” (illegitimate).

András Csiszár, a noble widower from Csetnek, wedded Mária Pongrácz at the town’s Lutheran church on July 8, 1807. The relationship of the 65-year-old man and the 28-year-old maiden was not new. Mária had served in the house of her future husband, as attested by a baptismal register from three years before. The new-born daughter of Mária Pongrácz, also named Mária, was baptized on December 19, 1804, and was entered into the baptismal register by the pastor as illegitimate. In all likelihood, the child’s father was the head of the household, who had been a widower for six years. This assumption is supported by the crossing out of the “spurius” qualifier after the wedding. Two years later the couple’s first legal child was born, and was later buried when she was only eleven months old. The husband died in February 1811 at the age of 68. Mária Pongrácz, who became a widow at 33, never remarried. Nevertheless, her name appears in the baptismal registers three more times: she had three further children, all registered by the pastor as illegitimate.

Two pages from birth registry of evangelical church in Csetnek: 1683 and 1755.

Stepsiblings and half-siblings

Because of the high adult mortality rates, children also frequently found themselves in new life situations. These situations could be tough to adapt to, and the mortality rate of underage children whose mother died subsequently doubled. However, if they found a place in the mosaic family, their chances of surviving to adulthood did not differ from that of those who lived with their blood parents.

The first-born daughter of István Getzeg, Zsuzsanna, was born on August 6, 1743. She lost her mother when she was five, and soon afterwards they buried her smaller brother. In the following fourteen years she had four new mothers, and at least four half siblings who all died at a young age. (Every one of Zsuzsanna’s stepmothers married as maidens, and none of them brought stepsiblings to the family). When she married András Boldis from Hámorfalva, she was her father’s only living child (although three years later another daughter was born from her father’s fifth marriage, who may have reached adulthood.)

The example of Zsuzsanna clearly reflects how many times a surviving child had to face family tragedies. As a small child, she saw the death of her siblings, her blood mothers and stepmothers. She had to learn to cope with the emotions related to the acceptance of her new parents, step and half siblings. It is very likely that as an adult, she had to relive the same life events: she buried her children, as well as probably her husband, and then it was she who had to make decisions…

The fate of orphans was a gratifying topic for literature and fine arts at all times. These works had a good chance of receiving positive feedback.

The fate of orphans was a gratifying topic for literature and fine arts at all times. These works had a good chance of receiving positive feedback.

Thomas Benjamin Kennington: Orphans (1885)

Follow us on Facebook to get notified of new posts!